-

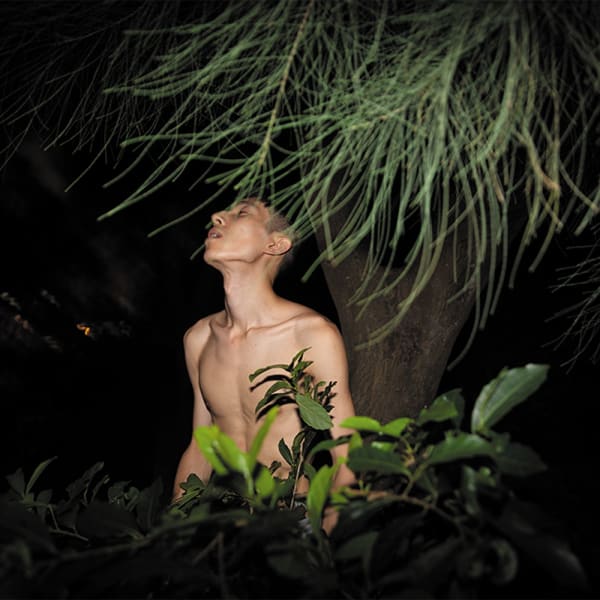

Ivana Bašić

-

Roland Biermann

-

Kurt Chan 陳育強

-

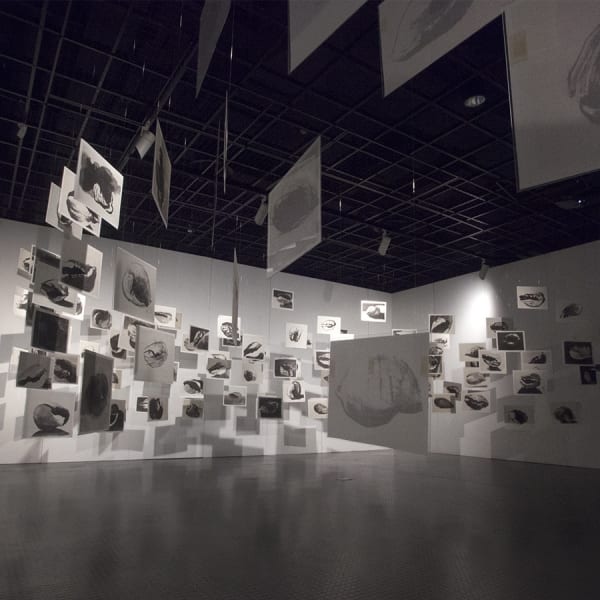

Chen Hui-Chiao 陳慧嶠

-

Cheung Yee 張義

-

Chou Lu Yun, Irene 周綠雲

-

Jes Fan 范加

-

Fong Chung-Ray 馮鍾睿

-

Juan Ford

-

Ho Sin Tung 何倩彤

-

Hu Chi-Chung 胡奇中

-

Steph Huang 黃麗音

-

Phoebe Hui 許方華

-

Yutaka Inagawa

-

Dew Kim

-

Kwok Hon Sum 郭漢深

-

Lan Zhenghui 藍正輝

-

Li Gang 李綱

-

Li Hao 李皓

-

C. N. Liew 劉慶倫

-

Lin Yusi 林于思

-

Crystal Liu

-

Cathy Lu

-

Meghann Riepenhoff 梅根·瑞普霍夫

-

Green Mok 莫育權

-

Qin Chong 秦沖

-

Qin Feng 秦風

-

Qin Wen 秦文

-

Qin Xiaoshi 覃小詩

-

Shi Jinsong 史金淞

-

Tang Chang 陳壯

-

Tseng Chien-Ying 曾建穎

-

Juan Uslé

-

Wang Chuan 王川

-

Wang Zhiyuan 王志淵

-

Wu Shan 吳杉

-

Xiao Bo 蕭搏

-

Yan Shanchun 嚴善錞

-

Yao Hai 姚海

-

Yeh Jen-Kun 葉仁焜

-

Rachel Youn

-

Young-Sook Park 朴英淑

-

Zhu Yiyong 朱毅勇